"We are tough on ideas and kind to people."

- Tom Ginsburg, Professor, University of Chicago (2023), Convocation Address

"It doesn't take much to become a successful artist. All you have to do is dedicate your entire life to it."

- Banksy

"When you think everything is someone else's fault, you will suffer a lot"

- Dalai Lama

"A black belt isn't someone who never gets hit. A black belt is someone who gets hit and doesn't care."

- Anonymous martial arts instructor (c/o Lyn Alden) (2023)

December 2023

Dear Fellow Investor,

Before embarking on the first Trans-Antarctic expedition in 1914, Ernest Shackleton, Captain of the Endurance, needed to recruit a crew. He settled on the following newspaper advertisement:

“Men wanted for hazardous journey. Low wages, bitter cold, long hours of complete darkness. Safe return doubtful. Honor and recognition in the event of success.”

Shackleton chose his men based on character and temperament, as much as technical ability. Distributing chores equally among officers, scientists, and seamen, his anti-hierarchical approach to management, revolutionary at the time, bred fierce loyalty. Perhaps most distinctive was Shackleton’s mindset towards each part of the journey, no matter how arduous: “I get to do this,” never “I have to do this.” Infectious, energizing, and inspirational, Shackleton’s mindset, it turned out, was lifesaving.

The history of the Endurance, in brief:

Departing Britain in August 1914, the Endurance got stuck in Antarctic ice the following January. Shackleton had no choice but to wait, and hope, for the southern spring to thaw the ice. After nine torturously patient months, the ice finally thawed. Instead of freeing the ship, it unexpectedly crushed the hull. Shackleton ordered “abandon ship” and the crew set up camp on an ice floe, hoping to eventually drift to safety. That didn’t happen. Six grueling months later, in April 1916, the ice floe began breaking apart. Jumping quickly into lifeboats, the crew survived a harrowing five-day journey to the nearest land mass, only to find a brutally inhospitable place with virtually no chance of discovery by rescuers.

Facing almost certain eventual starvation if they stayed, waited, and hoped, Shackleton took off with a five-man subset of his crew on a makeshift open-boat journey, seeking a known whaling station 720 miles away. A few weeks later, with their destination tantalizingly in sight, the crew encountered a hurricane, which they later learned sunk a 500-ton steamer. Somehow surviving the storm in their tiny craft, the team landed safely on shore the next day. Shackleton immediately began hiking to the whaling station, armed with technical equipment that consisted entirely of a single 50-foot rope. He traveled 32 treacherous miles over dangerous mountain terrain in 36 hours to reach his destination.

After quickly arranging a rescue vessel, Shackleton raced to recover his stranded Endurance crew, arriving in August 1916, 19 months after the ship was initially stuck. All survived.

In Shackleton’s original recruiting advertisement, he was clear about what each of his men would get to do. Hazardous journey, bitter cold, complete darkness, safe return doubtful. It all went according to plan.

I GET TO

As a businessman and provider for my family, there are many things I have to do, but that’s never been what I tell myself. I get to travel 4,000 miles to Europe and learn about aviation reinsurance from the best underwriter in the industry. I get to head downtown and learn about longevity insurance from the man who has sold more of it than anyone on the planet. I get to be part of the Investment Committee, including for our Post War & Contemporary (PWC) Art strategy, democratizing access to a potentially valuable, previously inaccessible hard asset exposure for all Americans.

Stone Ridge is not the Endurance, but I also get to lock arms with my colleagues when our AUM was cut in half, from some hurricanes and lots of investor redemptions, and firm profitability evaporated. I get to evaluate what we missed when a fund launch, with two years of preparatory effort and high hopes…doesn’t launch. I get to be Executive Chairman of NYDIG when (almost) all of our mining clients default on their loans and the greatest fiat banker of his generation asks the State to shut bitcoin down.

I get to keeps me grounded and grateful. I have to makes me tired and bitter.

This year, in numbers incomprehensible to me, Stone Ridge made almost $3 billion in uncorrelated trading profits for our investors across all franchises, with no down months. While everyone at Stone Ridge can be proud of those numbers, perspective is vital.

First, nothing we’ve achieved this year is because of this year. Success, and failure, are lagging indicators. Mountain climbing disasters are always a series of small, seemingly inconsequential decisions that interact in unexpected ways, compounding exponentially. Success works the same way.

It is fashionable these days to say investment outcomes follow a Power Law. That’s technically true and soulless. At Stone Ridge, the compounding we’re after is in wisdom and trust in our relationships with each other. Life is much more satisfying when we realize that relationships also follow a Power Law, and invest accordingly.

Second, we let the simplicity of our business model be enough. The humility of our questions and the plainness of our actions – our undefended openness – may occasionally seem to border on irresponsible naivete, but we rarely cross that border. And even when we do, we have each other’s backs with such ferocity that we never fail to pull ourselves back to safety.

Our most sustainable competitive advantage may be our comfort in the simplicity of what we do. The egos of many, especially in our industry, prohibit paths they believe run the risk of external invalidation. “That’s all that you do?” We hear that exact phrase a lot at Stone Ridge. It’s always been fine with us.

Third, our profits were hyper-diversified because our risk management philosophy is sacrosanct. I will never lose sight of the fact that the very largest numbers, when multiplied by even a single zero, all end up in the same place. Our daily practices hone hyperawareness to the threat of non-linearities. Rain gives life. Flood takes it. Flood is just non-linear rain. At Stone Ridge, we fear market non-linearities because we know for sure we won’t know when they will arrive. Our only defense, and fortunately it’s a powerful one, is not a portfolio of uncorrelated businesses. It’s a portfolio of unrelated ones, many dependent on physical processes – earthquakes, hurricanes, natural gas coming out of the ground – not financial markets.

Fourth, the one financial market I’m ok being heavily exposed to – short – is fiat. Being called a “bitcoin maxi” is about as offensive to me as being called a “heliocentric maxi.” Satoshi helped us this year.

ALL YOU HAVE TO DO IS DEDICATE YOUR ENTIRE LIFE TO IT

While University of Chicago professor Eugene Fama’s groundbreaking work on market efficiency won him the Nobel Prize, his even greater contribution, in my view, was his work on the principal-agent problem. In exquisite theory – beautiful logic, no equations, Austrian tradition – Fama observed that, in corporate finance, ownership and control of a firm are separate. Shareholders own the firm. Employees manage the firm. Fama identified two heuristically addressable, but fundamentally unsolvable, problems with this setup: a) incentive alignment and b) information asymmetry. Thirty years later, my world view remains unrecovered from Fama’s classes, and his papers, on the principal-agent problem.

Employees and owners do not have identical incentives. Thousands of small and large firm decisions attempt to minimize the distance. Separately, as firms grow, it is impossible for all involved to have access to identical information all the time – i.e., information asymmetry. Management faces a continual trade-off in the information content they choose to factor into corporate decisions. If they seek to maximize it (e.g., ask all employees to report on everything they are doing, all the time), management conceptually has more information to make better corporate decisions, but the firm minimizes the benefit of employee specialization, impairing firm value. If management minimizes employee input (e.g., never distracting employees from their chosen tasks), they maximize the benefit of employee specialization, but at the expense of limiting the information content factored into critical management decisions. There is no right answer.

Corporate form, compensation structures, and even internal meeting practices are all examples of implicit outputs of firms confronting the principal-agent problem. In 1980, Fama wrote that agency costs are the central problem in corporate finance. I think he’s right. At Stone Ridge, we view agency costs as the central problem in asset management, and therefore the central problem in asset pricing. In the decades ahead, we will see if we are right.

“Though this be madness, yet there’s method in’t.”

– Polonius, Hamlet, on why Stone Ridge chose reinsurance as our first franchise

Every franchise we consider building requires two conditions, each necessary, neither sufficient. First, clearly identifiable principal-agent problems that uniquely partnering with Stone Ridge can help industry leaders minimize. Second, and related, access to sustainably valuable proprietary data, whatever the source.

Let’s consider two seemingly unrelated industries – catastrophe reinsurance and art – and, looking through the lens of the principal-agent problem, perhaps see more similarities than differences.

In 2012, before we had any AUM, we hand-collected the prospectuses of every catastrophe bond ever issued and painstakingly built a proprietary database of their characteristics. We learned a lot. Later, we accessed, with permission, the highly proprietary, multi-decade catastrophe quota share performance history of globally leading reinsurers, our partners. We learned more.

We were interested in two foundational questions: “How much does reinsurance return?” We had no idea. 2% a year? 20% a year? 30%? Second: “What are the characteristics of the cross-section?” That is, does selling protection against Florida hurricanes and Japan earthquakes have different expected return?

In traditional asset pricing models, catastrophe reinsurance – given its lack of correlation to the market – should not be “priced.” That’s a fancy way of saying it should not have an expected return above the risk-free rate. In addition, no part of the cross-section should be differentially priced. That’s a fancy way of saying that Florida and Japan reinsurance risk should have the same excess return (and it should be zero).

Our empirical research, and subsequent practitioner experience, revealed that both theoretical predictions – no risk premium and no cross-sectional differences – were materially, consistently, and globally false. Catastrophe reinsurance has had a (highly) positive risk premium and a predictably differentiated cross-section, with U.S. risk having (far) higher expected return than non-U.S. risk.

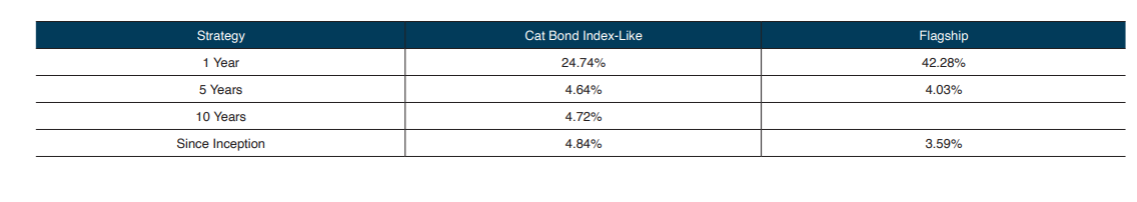

This year, our flagship reinsurance strategy is up 45%, the best performance of its 10-year life. Our cat bond index-like strategy is up 21% and its >10-year track record leads the industry.i Overall, Stone Ridge made well over $1 billion in reinsurance trading profits this year, on $1.7 billion of catastrophe premium, making Stone Ridge equivalent to about the fourth or fifth largest catastrophe risk bearing “reinsurer” in the world. This “ranking” on premium was pointed out to us about a week ago, but you cannot eat premium. We’re focused on the profits.

So, what’s going on with catastrophe reinsurance and with the Stone Ridge approach?

Principals invest money on behalf of themselves. Agents invest on behalf of others. Agents control the vast majority of invested wealth. They are the marginal investor, the one that matters. Agents allocate little, if any, of their principals’ money to reinsurance even though, over time, it has demonstrably better risk-return characteristics than stocks and bonds. Why? Perhaps incentive alignment, or lack thereof. Agents can lose their principals’ money with a reinsurance allocation, and in uncomfortably differentiated ways. Consciously or unconsciously, agents avoid what they perceive as unmanageable career risk, even at the expense of higher expected return for their principals. This keeps marginal capital away from reinsurance.

Turning to the cross-section, given an allocation to reinsurance, we do not observe agents allocating 100% to Florida-only risk, which offers, by far, the highest expected return in the industry. Instead, they choose a globally diversified reinsurance portfolio, with a correspondingly lower expected return. Why? Both allocations have identical (i.e., zero) correlation to the rest of the principal’s portfolio, so are almost equally de-risking. However, exposure to only a narrow slice of the reinsurance market – with a low, but higher probability of left tail loss – uncomfortably amplifies agents’ career risk, despite objectively higher expected return for their principals. Career risk = 𝑓[incentive (mis)alignment, principals, agents], a mathematical function that keeps marginal capital away from any narrow reinsurance market slice alone.

Next, let’s look at the value of proprietary data, an instantiation of information asymmetry. One hundred years ago, Munich Re and Swiss Re were the two largest reinsurers. Today, Munich Re and Swiss Re are the two largest reinsurers. The third largest, Hannover Re, self-identifies as the “new kid on the block” having started a mere 57 years ago. Reinsurance is (very) hard. Given this level of leadership longevity, form your own view as to the importance of proprietary data. In ours, we know why the Lindy effect is so powerfully operative in reinsurance.

At Stone Ridge, we don’t dare underwrite. We underwrite the underwriters. Our foundational approach is to partner, not compete, with the best underwriters in the world. With deliberate practice, high cadence connectivity, and internal private scorecards that matter deeply to us, we seek to earn and re-earn the right to be the most strategic risk-sharing partner to each of our cherished underwriting partners. Among many reasons for our invented business model, we view information asymmetry – e.g., the value of our partners’ proprietary data – as competitively un-overcomeable.

Consider that the most recent reinsurer to go public – a competitor to our globally leading partners – has underwritten unprofitably every year since its inception nine years ago, effectively financing its ROA (return on assets) at a +21% cost of funds. Over the same time-period, Hannover Re effectively financed its ROA at -3% running. Competition in any field with a 24% disadvantage in annual financing cost is not competition.

The newly public reinsurer trades near or below book value. Hannover Re generally trades between 2.5-3x book value. Over the last 25 years its stock has returned almost the same as Microsoft. Who said reinsurance isn’t interesting?

Finally, remember our flagship reinsurance strategy’s 45% return this year? That performance represents a source of both pride and sadness for us. Agents get appropriate criticism for buying high and selling low in all asset classes. Indeed, the well-known “buy high, sell low”-driven difference between the returns of equity mutual funds and the returns investors in those funds receive – “fund vs. investor return” – is enormous, and consistently enormous, over decades, at about 1%/year. This means agents forgo about one-quarter of the entire equity risk premium due to discomfort with holding ex-post losing positions, and misaligned incentives with principals. The same directional result, and for the same reason, exists in fixed income funds and, indeed, for every fund category.

The corresponding strategy vs. investor return for our flagship reinsurance strategy is 4.7%/year – the average investor made 4.7% less, per year, than our buy-and-hold investors, over ten years – the largest we have ever seen in asset management. As agents on behalf of our investors, that spread is heartbreaking to us. As the largest individual investors in the strategy – as principals – the flagship’s massive strategy vs. investor return dichotomy is the very source of why reinsurance is so attractive, for those who can act like principals.

“Life moves pretty fast. If you don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.”

– Ferris Bueller, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, on why art is the most recent Stone Ridge franchise

Fifty years before Stone Ridge began building our catastrophe bond database, a small crew at the University of Chicago founded the Center for Research in Security Prices (CRSP, pronounced “crisp”) and painstakingly began building the first ever database of stock returns. Today, with tens of trillions of dollars in equity mutual funds and ETFs, it may be hard to imagine that, in the not-so-long-ago-before-CRSP-times, no one knew the answer to the basic question: “How much do stocks return?” 2% a year? 20% a year? 30%? No one knew.

Using old newspapers and microfiche, the CRSP team hand-collected stock prices, dividends, stock splits, share counts, and corporate actions starting in the 1920s and going through the early 1960s. Once complete, for the first time ever, CRSP researchers could answer the question: “How much do stocks return?” Their answer turbocharged the mutual fund industry. Just as critically, CRSP gave researchers their first glimpse into the cross section – small cap vs. large cap, growth vs. value, positive vs. negative momentum – to more fully explore, and understand, expected stock returns, turbocharging both academic finance and the financial services industry.

Fast forward to today. Inspired by CRSP, and our own love of data, at Stone Ridge we have a proprietary database of art auctions going back to 1900 – ~8,000 artists, ~1,500 auction houses, ~300,000 sales – all painstakingly built and hand-collected.

We wanted to know two things: “How much does art return?” 2% a year? 20% a year? 30%? We had no idea. Second: “What about the cross-section?” That is, Old Masters vs. Impressionist vs. Modern vs. Post-War & Contemporary (PWC)? And, more granularly, what about Warhol vs. Picasso vs. Ruscha vs. Rothko?

We did not embark on this journey as fancy art people – though some pieces we own in our art strategy are stirringly magnificent – rather only to make money for our investors and ourselves. We also had a hunch about the art industry and the principal-agent problem.

Art market agents include the major auction houses, such as Sotheby’s and Christie's. They communicate with clarity that their motivation and remuneration is based on selling pictures. It is not their job to know the answer to the question, “How much does Picasso return?”, nor will they have any deep quantitative sense of fair value for any individual work. They have certainly never built a model of the last 500 Picasso sales, compared like-for-like transactions leveraging AI to objectively dimension similarities among necessarily unique works, or then thought to Ctrl-C/Ctrl-V-apply Case-Shiller’s groundbreaking real estate valuation methodology to art, so any and every relevant auction result anywhere in the world instantly updates fair values for every Picasso.

The agents are excellent at their job, they clearly love it, and they have encyclopedic knowledge of their areas of expertise. We love working with them. However, providing their clients with data-driven valuation model outputs for individual works, or even knowing the historical return of an artist or a genre, are simply not part of their incentives. The closest they can offer would be something like “Picasso’s market is strong right now” and even that would be via anecdote, not quantitative rigor.

Art market principals, aside from Stone Ridge via our art strategy, are about one thousand families at an institutional level. One of those families may be decorating a house in Aspen with an empty wall that they believe would benefit from a blue Rothko. They may buy that Rothko because it is blue, not because fair value is $10 million, and they paid $12 million. They will generally not know fair value – the amount or even the concept – and may not care. They certainly do not have access to proprietary data, AI-driven “comp” evaluation of the latest 50 trades of similar pictures, or unemotional, multifactor pricing models.

In art, amidst principals and agents with neither aligned incentives nor symmetric information, the market is worth almost $2 trillion – far larger, for example, than all private infrastructure funds, or all private real estate funds, combined.ii And it’s liquid, enough. Taken together, PWC artists trade $1-$2 billion per month.iii In addition, for the last 25 years, PWC art has annually returned just south of 12%, almost 5% more, per year, than the S&P 500.iv All huge, and hugely surprising, numbers to many.

So, what’s going on with PWC art and with the Stone Ridge approach?

First, our proprietary data reveals a fascinating, to us, monotonic relationship between vintage and expected return. In short, the newer the art(ist), the higher the average return. Old Masters (c. pre-1800) return about inflation, then each of Impressionist (c. 1850-1900)/Modern (c. 1900-1945), and PWC (1945 onward), sequentially, have had ~2-4% higher average return than their immediately preceding category.

On the demand side, academics could equally tell a behavioral or a risk-based story for these empirical results. Behaviorally, central bank money printing and globalization drive rapid billionaire creation and accelerating wealth inequality. In addition, for millennia, the wealthiest always covet cool new stuff. In art today, the “new new” major category is PWC. There is no reason to believe human nature will reverse any time soon.

From a risk-based asset pricing model perspective, PWC pictures are the small-value stocks of art: less information, more known unknowns, more unknown unknowns, more prone to crashes individually and as a group. Consider that PWC-artist Damien Hirst’s market not long ago dropped more than 80%, for entirely idiosyncratic reasons, and that decades ago, in back-to-back years, the entire market suffered a 63% drawdown.v It’s therefore rational that owning Hirst, or any individual PWC-artist, or holding “the market” as we seek to do in our strategy, requires high risk premium as compensation.

In contrast, Old Masters will always be Old Masters. We do not expect to ever learn any new information about da Vinci that would materially impact his market positively or negatively. It’s unlikely, for example, that we’ll open the New York Times one day only to discover that da Vinci, too, was cavorting with Jeffery Epstein, and watch his market collapse. Inflation seems about the right return level for Old Masters.

Second, on the supply side, art is the only investable asset class with a finite, and predictably decreasing, supply. At Stone Ridge, our strategy “collects” – i.e., institutionally invests in – about 50 PWC artists. 45% are dead. 46% are older and, most relevant for our purposes, no longer creating their small subset of iconic, institutionally investable pictures. 9% are active, potentially making important new work. Finally, a portion of our strategy’s investable universe gets donated to museums each year, taking that supply forever off the market, providing a gentle tailwind for PWC art generally, and our strategy specifically.

PWC art is also uncorrelated to stocks and bonds, and every other asset class we have ever examined. To build some intuition for this powerful empirical result, first imagine, instead, investing in sports collectibles. Competitive investors for a Mickey Mantle rookie card or a Babe Ruth bat will generally be U.S. males in a relatively narrow birth year range, with buying power subject to the vagaries of U.S. stocks, U.S. interest rates, and U.S. wealth. If the U.S. market crashes, Mantle and Ruth do too.

In contrast, wealthy people in every single one of the largest 50-100 countries want a Basquiat. Fine art has, and always has had, global demand. That allows us to reframe our business as an attractive, and we believe persistently mispriced, financial derivative: specifically, owning a diversified portfolio of the very top PWC artworks– our strategy already has exposure to ~125 works and ~50 artists – is like owning a best-of option. Did someone get wealthy today in Brazil or Australia or Oklahoma or France or…?

As long as the business cycles of the largest countries remain not perfectly correlated, or as long as enough governments remain fiscally or monetarily irresponsible – thereby “requiring” larger and larger fiat printing bailouts and acceleration of wealth inequality at the very, very top – PWC art buyers will remain their own economy. Factors that affect the NASDAQ or food prices simply do not affect them.

“Art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable.”

– Banksy

Our art strategy is new, small, and majority firm capital. As global debt/GDP soars and money printing accelerates, at Stone Ridge we want material, long-term exposure to an increasingly diversified portfolio of valuable, finite-supply, hard assets. Single family rentals (SFR), bitcoin, and now art. We’re getting there.

Art is just the latest example, which includes exactly 100% of the Stone Ridge franchises, of the first rule of product design at Stone Ridge: we build products we want ourselves. We have a world class art team, a peerless underwriting and risk-sourcing partner in Masterworks, and clients comfortably underexposed to hard assets and unexposed to art. Commercially, we will try to build this strategy into a big(ger) idea, one brick at a time. In the meantime, as principals, we will keep adding AUM ourselves throughout 2024.

WHEN YOU THINK EVERYTHING IS SOMEONE ELSE’S FAULT, YOU WILL SUFFER A LOT

At Stone Ridge, if you give an opinion and someone follows it, you must be exposed to its consequences. Our code is symmetry with our investors, having a share of the harm, and paying a material financial penalty if something goes wrong, regardless of the cause. In years we lost money in any franchise, nothing necessarily “went wrong,” in that successful risk premium investing requires occasional rough years, which must be unpredictable, else there would be no risk premium in the first place. However, in those years something certainly “went wrong” in the actual sense, the only sense that matters: we lost money.

Total acceptance of responsibility for our investment performance, positive or negative, requires maximal avoidance of industries dependent on political favoritism; that is, when lobbying, subsidies, or State-suppressed interest rates make the industry viable. “Stroke of the pen” risk – when a political or regulatory signature can make a business non-viable overnight – violates our most basic risk management discipline and affronts our firm culture. We are allergic to the negative energy of redistributive thuggery.

The solution, from first principles, is uncorrelated business, uncorrelated specifically to central bank manipulation of stock and bond markets. Instead of a central bank and a country, imagine a poorly run private company with enormous, unaffordable debt announcing to the market they were going to “cut rates”? Prices with low fidelity of information content are uninvestable. War Games-style, the only winning move is not to play.

For guidance, and a gameplan, we turn, again, to University of Chicago and to Fama, but this time to his Nobel Prize winning work on the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH). Fama (1970) defined three forms of market efficiency – weak, semi-strong, and strong – varying as a function of the information embedded in prices.vi In weak form market efficiency, prices reflect all publicly available information. Semi-strong form means prices adjust instantly, and accurately, to new public information. Strong form means prices reflect all public and private information.

For the last 50+ years, asset management strategies, firms, and entire industry segments have commercially succeeded or failed as a function of whether their chosen area of focus corresponded to, in hindsight, conditions of weak, semi-strong, or strong form market efficiency. There was no escape.

At Stone Ridge, we characterize our franchises as weak, semi-strong, or strong form uncorrelated. In strong form, franchise returns are unrelated, not just uncorrelated, to markets. Earthquakes and hurricanes (reinsurance), volumetric PDP (proven, developed, producing) well production (natural gas), and lifespan-linked income (Q1 2024 launch) are Stone Ridge franchises exhibiting strong form (un)correlation.

In semi-strong form uncorrelation, franchise returns can experience occasional short-term positive market correlation in crashes, but rapid repricing causes medium and long-term (un)correlation. Systematically selling very short-dated, out-of-the-money options to corn, wheat, and cocoa producers – i.e., selling (re)insurance-like risk transfer services – and systematically buying one-year duration prime consumer and small business loans (alternative lending) are Stone Ridge franchises that can be correlated over weeks or a few months, but historically and intuitively, not years. The size of their risk premium, combined with their repricing speed, cause those franchises to exhibit semi-strong form (un)correlation.

Finally, in weak form uncorrelation, franchise returns have systematic exposure to the inexorability of fiat debasement. Over short to medium intervals, fiat debasement can cause positive correlation. Stocks skyrocket in the early stages of hyperinflations (see, for example, Weimar, Zimbabwe, or Argentina), fooling holders every time of their increasing wealth, before it’s…gone. In contrast, coveted hard assets with finite supply have not subsequently crashed during hyperinflations, quite the contrary, driving their medium to long-term correlations to zero. PWC art, SFR, and bitcoin are Stone Ridge franchises with high beta to fiat debasement, thereby exhibiting weak form (un)correlation.

Not too hot, not too cold

Before embarking on the journey of a new Stone Ridge franchise, we must a) want the product for ourselves, b) believe no one has to lose for us (Stone Ridge and our investors) to win, c) successfully evaluate the role of the principal-agent problem in an industry, and d) empirically and intuitively satisfy ourselves with the franchise’s (un) correlation. However, even conditional on all of that, we still have one final, highly strategic, highly consequential decision: risk selection. That is, how much risk are we comfortable taking and, given that, how specifically shall we participate in the industry?

Internally, and perhaps too quantitatively, we call our approach “The Three Little Bears”: not too hot, not too cold. Along the dimensions of risk that we care about – market risk, regulatory risk, and reputational risk – “too cold” is too safe and not enough expected return. “Too hot” has high return potential, but too much uncertainty for our taste, particularly around known and unknown unknowns in stressed markets. We seek “just right” for us.

In alternative lending, this means no AAA student loans (too cold) and no subprime or Emerging Markets (too hot). Prime, U.S.-only is just right. In SFR, this means no homes over $500k (too cold) or under $150k (too hot). It also means no low-growth Detroit (too cold) and no boom/bust Seattle (too hot). $250-400k homes in steady San Antonio, for example, are just right.

Putting it all together, as a material source of expected firm income, we invest our firm’s balance sheet in all Stone Ridge strategies – alternative lending, reinsurance, SFR, energy, art, market insurance, and bitcoin – each developed based on the foundational principles outlined above.

Our empirical research shows that a hypothetical portfolio of all Stone Ridge strategies has produced meaningful return, low volatility, and low correlation to stocks and bonds. However, making actual, not hypothetical, balance sheet investments, at scale, across all Stone Ridge strategies, and adding fiat leverage, has earned more. The past five years, our annualized ROE as a firm has been 25%.

For us, access to our own strategies = a powerful reason to be short fiat.

A BLACK BELT IS SOMEONE WHO GETS HIT AND DOESN’T CARE

“If I was the government, I’d close it down.”

– FDR Jamie Dimon (April 1933 December 2023), on gold bitcoin

In April 1933, FDR gave Americans less than thirty days to “turn in” their gold or face up to 10 years in prison. The price of gold is ~100x higher today. And legal. Governments are persistently incompetent capital allocators and always impotent, eventually, against the will of their people.

In 1933, what caused the leader of the greatest country in the world to fear a yellow, inanimate object? Perhaps the same thing that 90 years later causes the greatest banker of his generation to fear digital, inanimate “blocks” created every 10 minutes.

The power to create money – via printing (central banks) or credit creation (commercial banks) – is simply too intoxicating to relinquish for anyone not named Milei. To bitcoiners, the hysterical wails “ban it!” or “close it down” are as boringly predictable as they are, Conute-like, irrelevant. It’s hard to point a gun at an idea, or at a passphrase in my mind, especially one I may have forgotten.

The “close it down”-crowd should know better. We do not get our rights from the government. The Constitution limits what government can do, not what the People can do. We fought a Revolution and founded a new country based on decentralization, free markets, property rights, and individual liberty. Quasi-anarchistic, the Revolution was, most of all, against strong central government, the exact kind that would seek to ban something worth far less than 1% of the national wealth and chosen freely by the People.

In contrast to bitcoin, fiat represents government-sanctioned counterfeiting. Printing little pieces of unbacked paper and trying to pass them off as money? Fiat is an economic paradigm premised on the plunder of time from the unfavored many not directly downstream of the State’s monetary spigot. No wonder those in charge love it.

Counterfeiting should be illegal regardless of whether the Xerox machine is government or privately owned. The only monetary difference is the size of the confiscatory audacity. The US Treasury estimates $70 million in counterfeit bills are in circulation. Since 2020, the Federal Reserve has Xeroxed a fresh, crisp $6 trillion.vii

“If I buy bitcoin…are you buying air? No underlying asset backs it up, it’s simply a matter of belief.”

– Elizabeth Warren (2023)

Bitcoin’s security is enforced by far more power than most entire countries produce. That’s not a matter of belief. Buying bitcoin is buying what bitcoin is backed by: an almost incomprehensibly vast amount of stored energy in its blockchain, more than a decade of 24/7, decentralized, Proof of Belief Work. Not air.

The free market only buys power for what it finds valuable. Right now, that’s about $811B of bitcoin.viii Like an innocently naïve six-year-old on Christmas morning, our nation’s first federal crypto law – from FinCEN in 2013 – called bitcoin virtual and Santa fiat real. Reality doesn’t care if you believe in it. Fiat is credit. Bitcoin is money. When FinCEN gets older, they’ll figure it out.

In a battle between the claws of the State and the invisible hand of the market, we can forgive the confused who believe they’re in power. The State excels at being certain. Certainty is different than truth. Once, the State said the sun revolved around the earth. Today, bitcoin is air. I wonder if wet streets cause rain?

"Everything that can be invented has been invented. We don’t need more digital currency.”

— Charles Duell Gary Gensler, Chairman of the US Patent Office SEC (1899 2023), questioning why the US needs a patent office bitcoin

Government officials wield tremendous power. They should be respectful and restrained. The ethics of the job demand personal “we don’t need”-like opinions be kept to themselves, and never influence their official actions.

The propulsive tentacles of the SEC Chairman’s extralegal agenda – yes bitcoin, but also share buybacks, corporate disclosure, private markets, securitization, security lending, predictive data analytics, much more – have ceaselessly sought expansion beyond legitimate boundaries. Taken together, in the public words of a heroic fellow Commissioner, his agenda reflects a “loss of faith that investors can think for themselves.” We can.

Fortunately, we live in a Constitutional democracy with an ingenious system of checks and balances on government power. They are working beautifully. In the past year, Courts have repeatedly defeated the Chairman’s agenda:

“Unlike regulatory treatment of like products is unlawful.” “Treating similarly situated parties differently is at the core of unfair discrimination.” “You cannot have it both ways…it is illogical for the rule simultaneously to accept and to reject the reasoning underlying the… benefit.” “Your actions are contrary to Constitutional right, arbitrary and capricious, and without observance of procedure required by law.” (Note: “arbitrary and capricious”, legally, means “without consideration or in disregard of facts or law” (Black’s Law Dictionary)

The Chairman’s personal opinions regarding what the entire country needs, or does not need – including bitcoin – do not matter. More SEC defeats are likely. All will be ok. In the meantime, black belts, and bitcoin, don’t care.

Bitcoin is not risky. Fiat is risky.

Over the last one, three, five, and ten years, long-term fiat savings (20Y+ US Treasuries Index) has cumulatively returned 2%, -33%, -8 %, and 24%, respectively.ix Over the same time-periods, long-term non-fiat savings, bitcoin, has cumulatively returned 156%, 46%, 1,052%, and 5569%, respectively.x Which one is risky? Which one is “backed by air”? Which one should we “close it down”? Which is the one “we don’t need”?

Since 2017, bitcoin has been Stone Ridge’s treasury reserve asset because of my extreme aversion to risk. We run net short USD – which is fancy way of saying we net borrow fiat – to pay bills and make investments. We save in bitcoin.

It would be impossible to overstate the corporate advantages of being on the Bitcoin Standard. Since 2017, we’ve doubled our franchises to ten, more than 10x’d our trading profits, and delivered 25% annualized ROE for our shareholders. Our firm compensation, rent, and total expenses are up 89%, 119%, and 69%, respectively, in fiat, and down 36%, 26%, and 43%, respectively, in bitcoin.

The more fiat we make, the more bitcoin I buy. You cannot print bitcoin.

“The first rule of Fight Club bitcoin is you do not talk about Fight Club price.”

– Tyler Durden, Fight Club, instructing new bitcoiners that we do not talk about bitcoin price

In a world of State money increasingly debased, censored, and surveilled, bitcoin represents optimism, fairness, justice, truth, and beauty. As the People’s money, bitcoin is unstoppable by borders, devaluation, censorship, or mass surveillance. “Privacy is necessary for an open society in the electronic age,” once wrote a very wise man.xi Please re-read that sentence a few times. Better yet, read the whole essay, increase your resolution on why Church, Money, and State must be separate, and the reason for the first rule of bitcoin then becomes obvious. I don’t mind if you come to bitcoin for the price. I just hope you stay for the principles.

TOUGH ON IDEAS, KIND TO PEOPLE

What makes a great firm? The intense, strenuous, and constant intellectual activity of the place, in which every colleague thinks for themselves, and has agency to execute their areas of personal responsibility. When you walk around, the air is electric.

At Stone Ridge, we recruit for wisdom-loving wonder, a necessarily joint activity. One colleague may put forth ideas and another may criticize, but there must be an attempt to think creatively together, whether within, or across, the permeable boundaries of our franchises. Excellence in creativity requires courage, sympathy, goodwill, and trust. In a word, belonging. Creativity is impossible without intellectual friendship.

When it comes to expertise, we never pretend we have it when we do not, but we are equally unafraid of its absence. I view my main responsibility as helping to create conditions that facilitate uncluttered thinking, rapid learning, and intellectual hunger, not fear, that we do not know what we do not know. In every field, there have been debates in which intelligent, well-meaning people took positions that, with the benefit of hindsight, were laughable. At Stone Ridge, we have been wrong before and we will be wrong again. The ideas must be the authorities, not the people.

Merit is our oxygen. We scrupulously insist that the most demanding recruiting criteria must always remain non-negotiable. I could not care less how anyone on our team worships, votes, or looks. They just have to be awesome.

“Retention or promotion must eschew convenience, friendship…no decision should permit consideration of the avoidance of hardship which might confront the candidate if a favorable decision is not made…favorable decisions should not be rendered on the grounds that evidence is not sufficient for a negative or positive estimate of future accomplishments…the insufficiency of such evidence is indicative of the candidate’s insufficient productivity…care must be taken to avoid regard for the rights of seniority in promotion…consideration should be given only to quality of performance, and age should be disregarded.”

That passage is from the Criteria of Academic Appointment, University of Chicago Faculty Committee (1970), but might as well be from the non-existent Stone Ridge Recruiting and Retention manual today.

“I get to” part II

We have never had, and never will have, an HR department. I prefer common sense. I’m also convinced “no HR” is a big part of why we achieved the statistic I care most about, and will never take for granted, in 2023: under 1% voluntary turnover. Powered by genuine idealism and unbounded optimism, I’ve yet to find the upper limit in my estimate of the potential of the people I get to work with.

“No HR” frees us to dream about how well we can treat each other. And to have off-market policies. We don’t meter vacation and encourage a lot of it. We offer unlimited maternity and paternity leave, and strongly encourage people to take lots of time off to enjoy that magical time with their family. We pay for self-improvement programs any employees want to enroll in. And, annually, we do a detailed competitive analysis to make sure we have what we believe to be industry-best Travel & Expense (T&E) policies. We simply expect our team to respect the firm’s generosity when they travel. They do.

Until earlier this year, my personal favorite policy was our bereavement policy. If a family member of any employee passes, our team of administrative assistants collectively spring into action to help with the travel logistics, if any, for the employee, and anyone in their immediate family, to attend the funeral. The firm also insists on paying for all travel and lodging expenses for all family attendees. Consider a non-executive Stone Ridge employee that grew up in a faraway war-torn country with a large immediate family, raised solely by his grandmother, who had just passed. Our policy could be (and has been) the difference between he and his entire family being able to pay their final respects in person, or having to pick and choose who gets to go. While, of course, not the reason for the policy, the private letters I’ve received from impacted family members afterwards are among my most treasured possessions.

Earlier this year, my favorite policy changed. At a firm happy hour in the spring, I overheard a star on our operations team discussing the cost of college with a group of colleagues. A new dad with two kids, 5 and 3, he said, “I’d love for my kids to go where I went to college, but it now costs $80,000/year. I can’t even imagine what it will cost when it’s time for my kids to go. My wife and I are already discussing that we won’t be able to afford it.”

I walked home that evening ruminating on what I overheard and had an idea. “What if?”, I thought. I mulled the idea in my head for a few months, mentioning it only to my wife, my assistant, and one colleague. They each were totally shocked, totally supportive, and asked the same question: can you afford it? I was pretty sure we could, but I was absolutely sure that if I did a detailed analysis, the exercise would ruin it for me, and I wouldn’t go forward.

At the next firmwide meeting after I was ready, I briefly told the story of the happy hour conversation I overheard and my subsequent ruminations. I then gathered myself, took a very deep breath, and announced the following to my colleagues: “For anyone who works at Stone Ridge for at least ten years, the firm will pay for your kids’ college.”

I continued, emotions now rising in the room, as my colleagues’ incredulity turned to life-changing astonishment, “I have not run a detailed analysis about whether we can afford this, but I think we can. I would just ask all of us commit to each other that if this policy ever becomes challenging for the firm to pay for, can we all agree to just work harder?” Screams, cheers, tears.

I left the room, emotionally overcome, with my assistant’s guiding arm around my shoulder. I couldn’t stop thinking, “I get to do this.”

OUR PARTNERSHIP

As we enter 2024, our tanks are filled with energy, gratitude, and inspiration. We innovate to prepare for an uncertain future, in pursuit of our mission: financial security for all.

Stone Ridge is most proud of the 50/50 partnership we have with you, our investors. We are on the path together. You contribute the capital necessary to propel and sustain groundbreaking product development. We contribute our collective careers’ worth of experience in sourcing, structuring, execution, and risk management. Together, it works. In that spirit, I offer my deepest gratitude to you for sharing responsibility for your wealth with us this year. We look forward to serving you again in 2024.

Warmly,

Ross L. Stevens

Founder, CEO

i 2023 returns as of 12/29/2023.

ii Source: Credit Suisse, Deloitte, Masterworks, McKinsey.

iii Source: Art Basel UBS 2022. Volume is auction volume plus dealer volume. Auction volumes are actuals. Dealer volumes are

estimated by scaling auction volume by the market-wide proportion of auction versus dealer volume.

iv Source for art returns: Index of public auction sales of PWC art constructed using the Case-Shiller methodology. Returns exclude any fund fees or expenses but include the auction buyer’s premium if applicable. Data are for the 25-year period ending 2022. Source for S&P 500 Returns for the same period: Bloomberg.

v Source for Damien Hirst: Artprice artist’s index. Source for the market: Index of public auction sales of PWC art constructed

using the Case-Shiller methodology (see above).

vi Fama, Eugene F. “Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work.” The Journal of Finance, vol. 25, no. 2,

1970, pp. 383–417. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/2325486. Accessed 27 Dec. 2023.

vii Money supply (M2) increased money supply (M2) from 15.3T in December 2019 to 21.7T in July 2022; currently 20.8T.

Source: Federal Reserve Economic Data as of 11/30/2023.

viii Source: Bloomberg as of 12/26/2023.

ix Source: Bloomberg as of 12/26/2023.

x Source: Bloomberg as of 12/26/2023.

xi Hughes, Eric, “A Cypherpunk’s Manifesto,” 9 March 1993. Available at https://www.activism.net/cypherpunk/manifesto.html.

Accessed 26 December 2023.

___

The bitcoin section is inspired by the work of many authors, especially Robert Breedlove and Murray Rothbard, with certain concepts and select phrases from their various writings and on-topic podcasts. The section on Stone Ridge people and recruiting is, in part, inspired by, and uses select phrases from, The Chicago Canon on Free Inquiry and Expression.

___

Standardized returns as of most recent quarter-end (9/30/2023).

Cat Bond Index-Like strategy inception 2/1/2013; Flagship strategy inception 12/9/2013. Results reflect the reinvestment of dividends and other earnings and are net of fees and expenses. Performance data quoted represents past performance; past performance does not guarantee future results.

Risk Disclosures

This communication has been prepared solely for informational purposes and does not represent investment advice or provide an opinion regarding the fairness of any transaction to any and all parties nor does it constitute an offer, solicitation or a recommendation to buy or sell any particular security or instrument or to adopt any investment strategy. Charts and graphs provided herein are for illustrative purposes only. This communication is not research and should not be treated as research. This communication does not represent valuation judgments with respect to any financial instrument, issuer, security or sector that may be described or referenced herein and does not represent a formal or official view of Stone Ridge.

It should not be assumed that Stone Ridge will make investment recommendations in the future that are consistent with the views expressed herein, or use any or all of the techniques or methods of analysis described herein in managing client accounts. Stone Ridge and its affiliates may have positions (long or short) or engage in securities transactions that are not consistent with the information and views expressed in this communication.

There can be no assurance that any investment strategy or technique will be successful. Historic market trends are not reliable indicators of actual future market behavior or future performance of any particular investment, which may differ materially, and should not be relied upon as such. Target or recommended allocations contained herein are subject to change. There is no assurance that such allocations will produce the desired results. The investment strategies, techniques or philosophies discussed herein may be unsuitable for investors depending on their specific investment objectives and financial situation.

Hypothetical performance results are presented for illustrative purposes only. Hypothetical performance results have many inherent limitations, some of which, but not all, are described herein. No representation is being made that any investment product or account will or is likely to achieve profits or losses similar to those shown herein. In fact, there are frequently sharp differences between hypothetical performance results and the actual results subsequently realized by any particular trading program. One of the limitations of hypothetical performance results is that they are generally prepared with the benefit of hindsight. In addition, hypothetical trading does not involve financial risk, and no hypothetical trading record can completely account for the impact of financial risk in actual trading. For example, the ability to withstand losses or adhere to a particular trading program in spite of trading losses are material points which can adversely affect actual trading results. There can be no assurance that the models on which any hypothetical performance results contained herein may be based will remain the same in the future or that an application of the current models in the future will produce similar results because the relevant market and economic conditions that prevailed during the hypothetical performance period will not necessarily recur. There are numerous other factors related to the markets in general and to the implementation of any specific trading program that cannot be fully accounted for in the preparation of hypothetical performance results, all of which can adversely affect actual trading results. Certain of the assumptions have been made for modeling purposes and are unlikely to be realized. No representation or warranty is made that all assumptions used in achieving the returns have been stated or fully considered. Changes in the assumptions may have a material impact on the hypothetical returns presented.

The information provided herein is valid only for the purpose stated herein and as of the date hereof (or such other date as may be indicated herein) and no undertaking has been made to update the information, which may be superseded by subsequent market events or for other reasons. The information in this communication may contain projections or other forward-looking statements regarding future events, targets, forecasts or expectations regarding the strategies, techniques or investment philosophies described herein. Stone Ridge neither assumes any duty to nor undertakes to update any forward-looking statements. There is no assurance that any forward-looking events or targets will be achieved, and actual outcomes may be significantly different from those shown herein.

Information furnished by others, upon which all or portions of this communication are based, are from sources believed to be reliable. However, Stone Ridge makes no representation as to the accuracy, adequacy or completeness of such information and has accepted the information without further verification. No warranty is given as to the accuracy, adequacy or completeness of such information. No responsibility is taken for changes in market conditions or laws or regulations and no obligation is assumed to revise this communication to reflect changes, events or conditions that occur subsequent to the date hereof.

Nothing contained herein constitutes investment, legal, tax or other advice nor is it to be relied on in making an investment or other decision. Legal advice can only be provided by legal counsel. Before deciding to proceed with any investment, investors should review all relevant investment considerations and consult with their own advisors. Any decision to invest should be made solely in reliance upon the definitive offering documents for the investment. Stone Ridge shall have no liability to any third party in respect of this communication or any actions taken or decisions made as a consequence of the information set forth herein. By accepting this communication, the recipient acknowledges its understanding and acceptance of the foregoing terms.